/lu:talika/

Pabllo Vittar, a Drag Queen Pop Star

Pabllo Vittar, a Drag Queen Pop Star

Essay

Catarina Bernardi

This dissertation focuses on exploring the art of drag as a form of challenging social-political structures. It has a post-structuralist approach, which analyzes the construction of gender as a concept, how cultural productions can help to create ruptures in society and what role the individual’s agency has over this transgression. This theory is then seen in practice through the drag performance, and specifically, through considering the career, agency, and production of the drag queen Pabllo Vittar.

Introduction

How and why is the art of drag transgressive? Does it replicate gender norms? Or does it challenge gender performance? The drag universe it’s broad and complex. Due to its increasing popularity, it has been at the center of discussions in and out of the LGBTQ+ community. Considering the complexity and diversity of drag and the multiple impacts it has had on society, this dissertation will focus on analyzing a specific phenomenon in the drag movement: how it moved from marginal to the mainstream.

More specifically, this work aims to answer what are the social apparatuses drag queens used to make this transition. I’ll be looking at this phenomenon with a post-structuralist approach, and finding ways to use these theories to understand our contemporary reality. To make a more in-depth study, I decided to focus mainly on drag performers that are men doing female impersonations, and analyzing the role they have as individuals over their artistic productions. My case study is the famous Brazilian drag queen Pabllo Vittar, and I’ll consider her cultural production and integration into mainstream culture.

This specific subject within the drag community interests me as a creative because it allows me to explore minorities’ representation and production in popular culture, through the lens of performance. As someone who is an active agent in producing creative work under the influence of societal power structures, I’d like to understand how drag as cultural production reflects issues regarding representation, agency, production, and the permeability of subcultures in mainstream culture. As an individual in society, I believe this study will help me understand how marginal cultures exist in society and how they can contribute to structural changes.

To lay out the theoretical framework of this dissertation, the first chapter Gender Identity & Subjectivity outlines the post-structuralist approach that this study has, going into key concepts – developed mainly by Michael Foucault – about subject and subjectivity in modern-day society. These concepts are the basis for the reader to understand how sexuality was constructed and, consequently, how gender was constructed and is performed – according to the work of Judith Butler.

Still following Foucault’s approach, the following chapter, Production and Agency, is focused on understanding how one can use freedom to have agency in cultural production inside a post-structuralist society. The chapter also examines the social apparatuses, described by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, that explain the assimilation of marginal symbols and icons into mainstream culture.

The third chapter gives a brief historical context of drag and how this art form puts into practice issues of gender performance, production, and agency described in the past chapters. This section also analyzes LGBTQ+ figures in Brazilian culture that preceded Pallo Vittar, describing their role of transgression and representation for the community.

The fourth chapter will go over the career, performance, production, and agency of Pabllo Vittar, showing how they used the social apparatuses previously defined to reach popular culture. There is also a comparison between Pabllo and two other Brazilian drag queens that began their careers at similar times and with whom Vittar shares a similar aesthetic. This observation will allow the reader to understand how the use of certain visual symbols, styles, and identities can help – or not – for a subculture to be permeable in mainstream society. In the end, the chapter studies how Pabllo’s performance is or isn’t transgressive and how it contributes to structural changes.

Figure 1: The drag queen Divina De Campo entering the DragCon UK in January 2020 (Fewings, 2020).

Finally, it is important to mention that this text will use the term LGBTQ+, instead of queer, because it recognizes the individual identification one can have (either as lesbian, gay bisexual, or/and trans), and has been taught to identify with by power structures that will be described in the first chapter. Nonetheless, the term LGBTQ+ does not fail to include those who agree with a more unifying approach to identity movements, present in the Q for queer and the +.

Chapter 1: Gender Identity & Subjectivity

“We’re all born naked and the rest is drag”

The quote above was coined by the famous drag queen RuPaul (2014). It encapsulates very well the idea that this first chapter introduces concerning gender performance and its implications. However, it is important to understand the context and theoretical framework where these ideas emerged – way before any reality TV show.

Post-Structuralism and the Subject

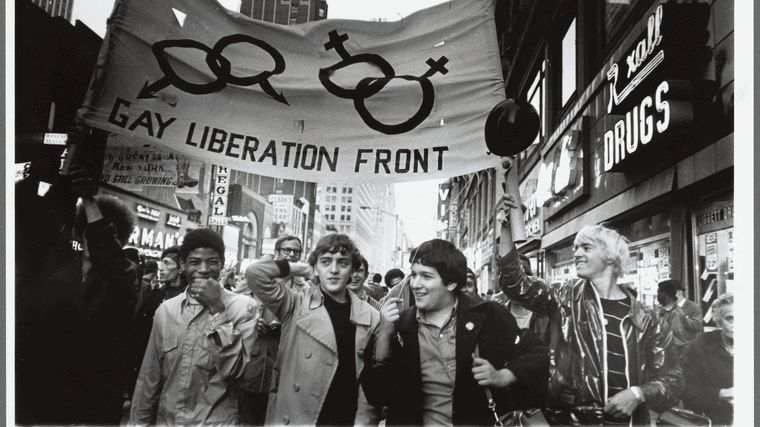

In the 1970s, society was coping with a big rupture of paradigms that emerged from the counterculture movements from the 1960s. Up until this point, structuralist theories, which analyzed macro structures in society – such as the economy and social classes – were very popular amongst scholars. However, the counterculture groups and the rise of identity movements (e.g. Stonewall, Second Wave Feminism, Black Panthers) brought to light the inability of structuralist theories in dealing with topics that require closer attention to the diversity that exists in society. From these observations, the post-structuralist movement began. Judith Butler (1990) defined this philosophical movement as one that rejects the totality and universality of binary structures, which operate to silence the ambiguity and plurality of language and culture.

Figure 2: Gay Liberation Front marching in New York, 1969 (Davies, 1969).

One of the thesis on which post-structuralist thought bases itself (Craig, 2005) is that no system can be self-sufficient in the way that structuralism suggests. That is because poststructuralists theorize that these systems exclude the participation of the subject, in a way that it becomes a passive object, incapable of agency. Michael Foucault challenges this structuralist assumption by reintroducing the concept of subject and subjectivity.

Foucault (1994, p. 10) argues that in modern society, the subject is a rational active agent, with political rights and moral responsibilities. They exist within a society, organized by power relations, which, simultaneously, broadens, and limits the subject’s experience according to the socio-historical moment that they exist. The subjectivity then lies in the dynamic relationship of becoming these different subjects, within what is possible to one’s reality. Subjectivity is not imposed, but it is offered to the individual, who is an active subject in becoming and incorporating the subjectivities.

This means that the system is not self-sufficient, but operates in a way in which the subjects collaborate for its maintenance. What guarantees this “operation” is power. According to Foucault, power is a productive force (Oksala, 2011, p.90). It is not to be confused with oppression, which can be a consequence of this force. Also, it should not be confused with domination, which is the consequence of the failure to interpret power as a relationship between free individuals. Domination is static, power is dynamic and productive. Fundamentally, it does not limit the human experience but creates a certain number of possibilities to which the subject will act and be subjected. The process in which power creates subjectivities is defined by Foucault as assujettissement (Heyes, 2011, p.159-160).

Subjectivity and sexuality

In the History of Sexuality, Volume 1 (1979) Foucault investigates the origins of society’s notions around sexuality. He identifies that it became a topic of interest around the 17th century, through Catholicism’ acts of confession. In the 18th century, there was a rise in psychiatric studies about sexual disorders, and some sexual practices were criminalized. These processes evidence the need for constant confession and assimilation of the individual’s sexual desires and identity. They form an account of multiple experiences built on the discourse that determines sexuality. This process of assujettissement is exemplified by Foucault (1990, p.43):

“As defined by the ancient civil or canonical codes, sodomy was a category of forbidden acts; their perpetrator was nothing more than the juridical subject of them. The nineteenth-century homosexual became a personage, a past, a case history, and a childhood, in addition to being a type of life, a life form, and a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and possibly a mysterious physiology.”

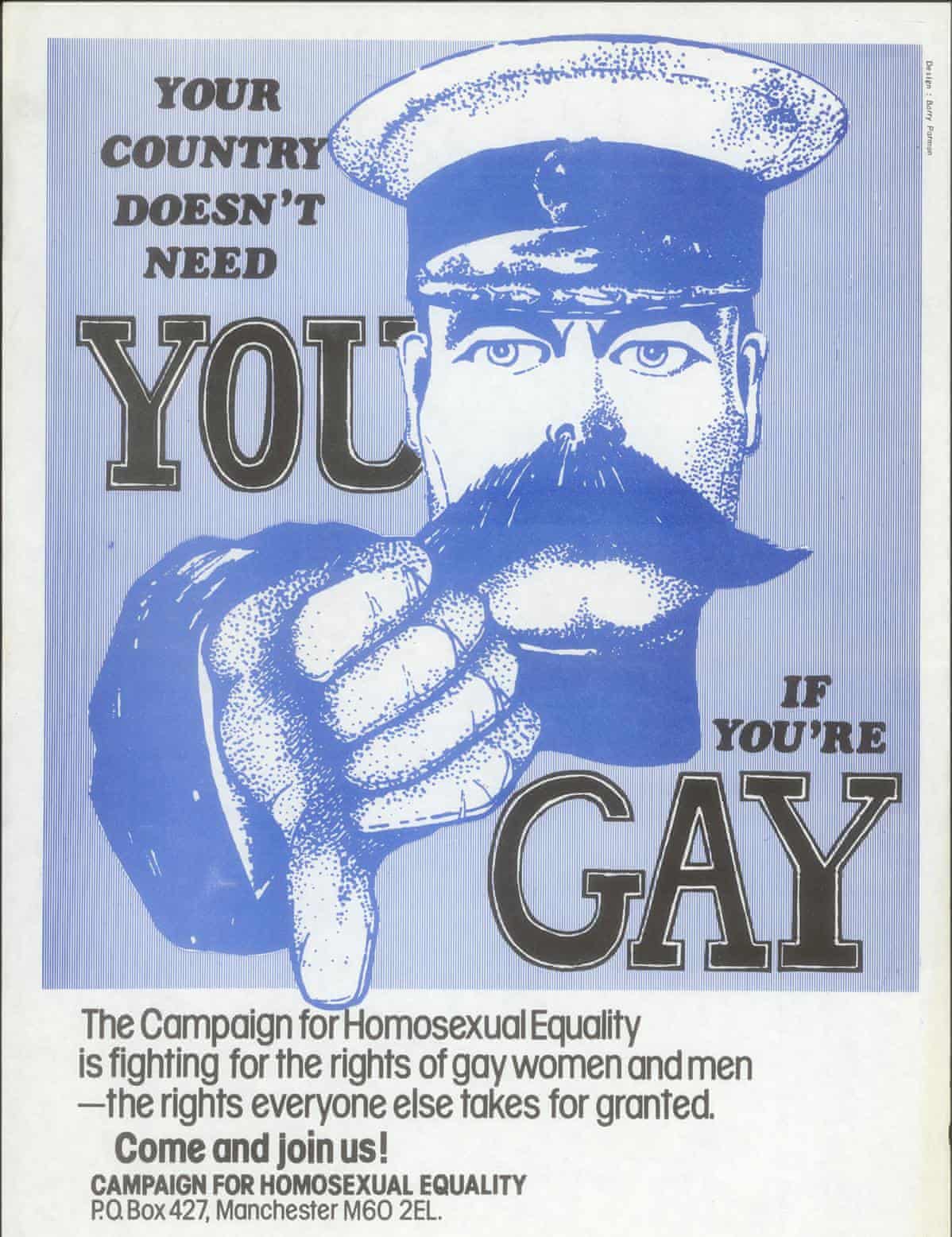

Figure 3: Poster for the Homosexuality Equality Campaign addressing inequality in the armed forces (London Metropolitan Archives, 2019).

Therefore, through the assujettissement, a new subjectivity is created, one which subjects are given the option to identify with or not. Nonetheless, this choice is not inherited, but fabricated. Choosing between one or the other (in this case, heterosexual or homosexual) doesn’t make one more or less natural than the other, since both subjectivities are fabricated.

The conceptualization of sexuality depends on the body. It is the body that is the physical manifestation and venue of the conditions expressed by a subjectivity. Here, sex is the key concept to conceive sexuality and the power it has over the bodies. In this context, what Foucault (1990, p.155) means by sex is derivative of the French definition of the word. It equally refers to the different anatomical structures (that differ from a male to a female), the common biological principle (present in both male and female), and the act of intercourse. This ambiguous definition only supports Foucault’s point in showing the arbitrary grounds on which sexuality was built.

Foucault recognizes the materiality of the body (1990, p.151), the biological and anatomical features it possesses. However, he is critical of the relation constructed between materiality and the idea of sex. This construct of sex allowed us to join anatomical features, behavioral patterns, and desires in a made-up unity that is the cause of the different kinds of sexuality. Also, sex was associated with reproductive science, giving the former equal scientific validation as the latter. Finally, if this sex is related to biological body features, it is deemed as natural, and therefore, not a product of a power relation (Oksala, 2011, p.92).

All of the theoretical benefits mentioned above made the construct of sex – and consequently, sexuality – normalized in society. Oksala (2011,p.91-92) analyzes this movement:

“The idea that “sex” is the scientific foundation, the true, causal origin of one’s gender identity, sexual identity, and sexual desire makes it possible to effectively normalize sexual and gendered behavior. Through scientific knowledge about one’s true sex, it is possible to evaluate, pathologize, and correct one’s sexual and gendered behavior by viewing it as either “normal” or “abnormal”.

Foucault’s theory about the construction of sexuality and its forged characteristics has given a theoretical basis for Judith Butler’s ideas around gender construction and performance. In the same way that there is no true sex, as cause and biological foundation of gender identity, the idea of gender itself formulated and regulated by power and knowledge relations.

This means that the fundamental idea that the female sex (for example) exists is the result of feminine behavior – behavior precedes biology; because one behaves like a woman, they will be seen as belonging to the feminine sex.

Gender construction and performance

Judith Butler (1988) uses Michael Foucault and a few other scholars to develop her theories around gender. One of them is Simone de Beauvoir. Butler uses Beauvoir’s famous quote “One is not born, but, rather becomes a woman” (Beauvoir, 2009, p.330) to exemplify how gender is not a stable identity, constructed in time through stylized repetition acts – in the same logic that Foucault’s discourses about sexuality and the assujettissement.

Neither sexuality nor gender has any biological or ‘natural’ grounds. Both concepts use the body’s materiality (features, physiological processes, desires, etc) to attach a social construction. To illustrate this, Beauvoir (2009) argues that to be a female is a biological fact with no meaning, but, to be a woman implies making the body complacent with the historical concept of what it is to be a woman. The body becomes the bearer of this subjectivity of “woman”, which includes a series of social symbols and behaviors produced by a power structure. These social symbols and behaviors are what Butler (1988, p.520) calls “stylized repetition of acts”.

Although Foucault and Butler share their views in the fabrication and maintenance of these subjectivities known as sexuality and gender, Butler takes a step further in her analysis, investigating how these structures are reproduced, applied, and act in society. That’s why she dedicates herself to studying the acts that constitute the gender, in other words, the acts that make up a gender performance.

Butler (1988, p. 526) will compare the stylized repetition of acts by which individuals perform gender to a role that an actor plays:

“Gender is a an act which has been rehearsed, much as a script survives the particular actors who make use of it, but which requires individual actors to be actualized and reproduced as reality once again”

By using this comparison to illustrate her theory, Butler is also affirming the agency an individual (or an actor) has over the performance (or the role). Similar to how a play only exists when being acted out, the reality of gender is dependent on performance. Gender only exists until its performance exists. This means that the agency of how gender will be performed belongs to the subject and that there are many different manners in which gender can be performed (as well as one role can be interpreted by actors in different ways). This is where lies the power of transformation. It relates to the concept of exercising freedom, suggested by Foucault (Taylor, 2011, p.4), which entails the navigation of the relations of power.

Returning to RuPaul’s (2014) quote that started this chapter, Butler addresses the transvestite figure (1988) by saying that it doesn’t only explicit the difference between sex and gender, but also challenges the difference between appearance and reality. If, as previously mentioned, the reality of gender is dependent on performance – in other words, what it ‘appears’ to be – then there’s no distinction between what is real and what is performed. It’s all drag.

Figure 4: The drag king Dom Valentim in a burlesque photoshoot (Valentim, 2019).

Chapter 2: Production & Agency

This chapter will expand this dynamic to a larger socio-cultural context, by discussing cultural production in a post-structuralist society and the agency the individual has over it.

Production

As Butler (1988) has described, to perform the female gender, one must use a series of symbols and gestures corresponding to what society identifies as “woman”. Some drag queens, who do a female impersonation in their act, use these same apparatuses to create this illusion. The collectiveness of the audiovisual symbols and social behaviors that communicate the idea of a woman is described by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (1987, p.257) as an assemblage.

The post-structuralist authors, who were contemporary to Foucault, used the term assemblage to contemplate an organization of elements that together possess a capacity (1987, p.257) – like the capacity to perform womanhood, for example. An assemblage is not preceded by a particular concept, and it is neither a random selection of ingredients since Deleuze and Guattari (Wise, 2005, p.77-78) emphasize that certain things can only co-exist in a given time and place.

Another principle of the assemblage is that its meaning and components are not fixed. The elements that compose an assemblage will be combined and de-combined according to variable values, subjectivities, and dogmas of a society in a given time and space. As the authors clarify (1987, p. 406):

“We will call assemblage every constellation of singularities and traits deducted from the flow-selected, organized, stratified in such a way as to converge (consistency) artificially and naturally; an assemblage, in this sense, is a veritable invention”.

Figure 5 (right) and 6 (left): On the right, the drag queen RuPaul (Duclos, 1995) using an assemblage of elements that during the early 90s were associated with female figures, such as long hair, big breasts, small waist, slim arms, etc. On the left, the drag queen Aquaria (2020), showing a contemporary assemblage that is still able to communicate femininity but allows for different symbols such as short hair, lack of breasts, and arms with strong muscles.

Deleuze continues his theory by claiming that assemblages form territories, which are not tied to a physical place but are rather created to evoke meaning. Much like assemblages, territories are not fixed and can be put together or apart according to the social-historical conditions (Wise, 2005, p.79).

It is possible to observe a practical example of this theory by analyzing some elements in the movie White Chicks (2004). The comedy is about the FBI Agents Kevin and Marcus Antony, who have to disguise themselves as the two Wilson sisters to investigate a crime. The assemblage of the Wilson sisters is made up of a series of visual elements – like hair, makeup, clothes, body shape, etc – and non-visual elements – like personality, behavior, tone of voice, etc. Together, these elements have the capacity of creating the illusion that Kevin and Marcus are actually Brittany and Tiffany Wilson. This assemblage creates the territory of what are the Wilson sisters, and different elements of it can evoke this meaning. One example is a scene where the FBI agents are in their hotel room, dressed as themselves when they hear a door knock. Marcus answers it, using Brittany’s voice – therefore using an assemblage – composed of voice pitch, word choice, intonation – to create the territory of ‘Brittany’ right then and there.

Figure 7 (right) and 8 (left): on the right, the FBI Kevin and Marcus as themselves, on the left, the pair performing as the Wilson sisters (White Chicks, 2004).

The constant creation of territories (or territorialization) is a systematic organization by which society functions, separating individuals by category (race, gender, social class, etc). These categories are what Foucault (1994, p.10) called subjectivities, to which individuals identify with and tie themselves to. However, the inconsistent aspects of territorialization create gaps and ruptures, which is where Deleuze (Albrecht-Crane, 2005, p.124) argues that variations occur. These variations – or deterritorializations – are essential to the creation of territories, because it is through them that new ideas, paradigms, and values are developed – in other words, new territories and new subjectivities.

This constant process of territorialization and deterritorialization is what Deleuze (Conley, 2005, p.172) defined as folding. Much like the physical process of folding paper or fabric, the Deleuzian act of folding implies in the socio-historical process that generates new ideas and movements, what he calls ‘folds’.

By analyzing Foucault’s work, Deleuze (1988, p.98) identifies how history is constructed not by a chronologic succession of events, but by constant and multiple folds (or, as Foucault puts it, “doubles”), as Conley (2005, p.172) mentions:

“He meant that what was past or in an archive was also passed – as might be a speeding car be overtaken or ‘doubled’ by another on a highway – but also mirrored or folded into a diagram”.

Every time a fold is created, a new relation is created. There are an inside and an outside, two sides of the same surface. The process of assujettissement (Heyes, 2011, p.159-160) is dependent on folding since it’s by having subjectivities that one separates themselves from the other. The ‘me’ will fit in a different subjectivity than the other, like a fold with an interior and an exterior (consecutively). However, when one sees similarities between themselves and the other (e.g. sharing the same sexual orientation), the individual re-folds and assimilates a new subjectivity (e.g. bisexual).

For Deleuze (Conley, 2005, p.173), folds are the social-historical device that allows change. It is by folding that resistance and transformation become a possibility, deterritorializing ideals constructed through current power relations.

Looking back at Butler’s gender performance theory, one can say that new ways of performing gender are created by folding the concept of what it is to be of a given gender. These folds happen according to how an individual or a group navigates the existing power relations of their socio-historical context (something that will be discussed in further detail later in this chapter). Also, this process once more exemplifies how the construction of gender is artificial and how it can be molded according to the ideals of a society in a given time.

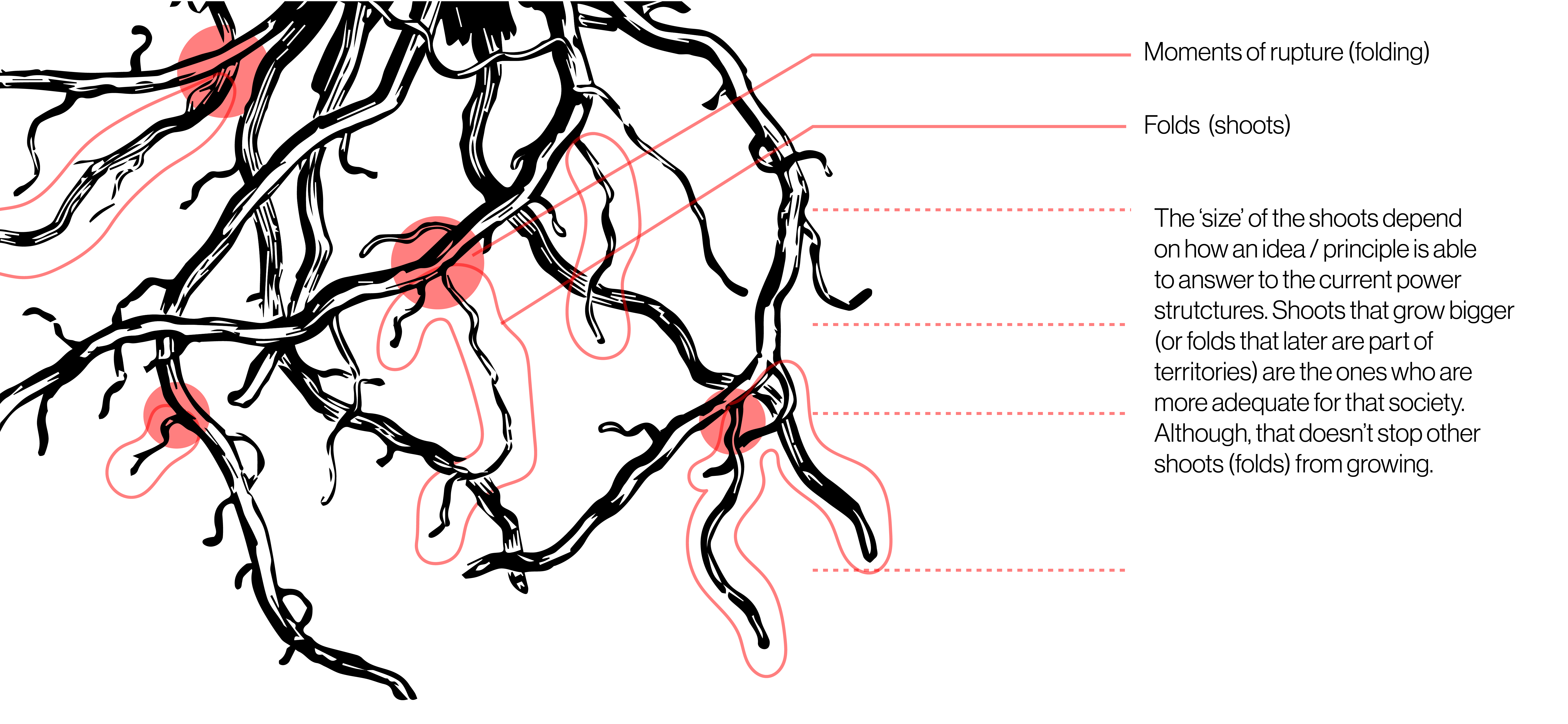

To analyze on a bigger scale how these folding processes occur in society over time, Deleuze, along with his fellow author Guattari (1988, p.8) considered the folding process occurring in society through time as a rhizome. This analogy was made to explain that, for the authors, there is no true singular origin of anything (idea, system, theory, structures, etc), but many co-existing horizontal possibilities (or shoots) that are created simultaneously according to the social-historical context. What will make some of these “shoots” grow more than others – in other words, some ideas to be more diffused in society – is how they represent the current values of society and how they work within the power structure of the time. Below, it’s a visualization of this process.

Figure 9: Infographic explaining the rhizome system according to Deleuze and Guattari (Personal archive, 2020).

Agency

Now that the panorama of how production takes place in society is set, it is important to understand the agency that an individual has over this production. Back to Chapter 1, it is appointed that Foucault (1994, p. 10) theorized that power relationships only exist within a system where individuals are free, since power is a productive force and not a restricting force – it creates a reality that can restrict an individual, but power is not restrictive in its essence.

Foucault (May, 2011, p. 71) developed this study going against two lines of thought: of metaphysical freedom – one which affirms that humans have total control over their minds and bodies; and of determinism – which declares that humans don’t have any control over their lives and it’s all determined by a higher power (being either the government, a deity, etc). The latter is incoherent according to the author’s view since it doesn’t consider the existence of rational active agents, which is an essential principle of Foucault’s post-structuralist theories.

Yet, the scholar is not affirming the existence of metaphysical freedom (May, 2011, p. 74). Foucault argues that our freedom is essentially tied to the socio-historical moment we live. It’s it that will determine what kind of restrains, manifested by power structures, are in place. Therefore, it would be incongruous to say that a person who lives in a specific time and place, where the current social policies restrain their living possibilities (e.g. a homosexual captured by the German during World War II (Mullen, 2019) ) has a freedom of will over their minds, bodies, and behavior. The present power structures train the bodies and minds of individuals to be complacent to their limitations, minimizing the chances of resistance or experimentations with other forms of living (May, 2011, p. 76)

Nonetheless, history is constantly shifting, through processes like folding, as previously described; and so are the power structures – since Foucault (Oksala, 2011, p.90) also highlights the dynamic principle of them. The conditions that limit one can be overcome (a homosexual living in modern-day Germany won’t face the same restraints as one existing in World War II). Here is where lies the author’s enthusiasm (1990, p.156):

“There is an optimism that consists in saying that things couldn’t be better. My optimism would consist in saying that so many things can be changed, fragile as they are, more arbitrary than self-evident, more a matter of complex, but temporary, historical circumstances than with inevitable anthropological constraints. “

For Foucault (Todd, 2011, p.112), freedom is not a matter of being (metaphysical) but a practice: the act of understanding and navigating the power relations that are in place. The conditions that are in place were created by the sets of principles that reign the current historical moment, which was also determined by previous experimentations of power, as a simultaneous co-dependent and dynamic process that occurs not by the force of any higher power, but by the act of rational active agents.

For this practice to take place, individuals must have (at least) partial knowledge of their conditions (which is obtained through critique (Foucault, 1997, p.125), a phenomenon that will not be discussed in this body of work). From there, one will prioritize which forces they deem acceptable and which ones are intolerable – that the individual will attempt to change. (Todd, 2011, p.80).

These changes (or explorations of the power relations) will happen as a consequence of a process of experimentation. Foucault (Todd, 2011, p.80) affirms that these experimentations are a practice of freedom since they exercise the agency the individual has over their condition, exploring the possibilities given to them. Although, these experimentations are not done with a clear response in mind. The consequences, being successful or not, can only be observed in retrospect. It is here that there’s a distinction between freedom and liberation. Freedom lies in the limbo of the uncertainty of experimentation, in the act of experimenting; liberation can be a consequence of those experimentations (Todd, 2011, p.81).

Deleuze and Guattari (1986) write about an example of experimentation: the minor. In their studies, the authors focus on analyzing the phenomenon of minor literature, but this concept can also be applied to other cultural productions.

Minor productions designate the works made by a member or a group belonging to a social minority. Its opposite would be the major productions, that circulate in a mainstream context and that are usually created by a member of a group belonging to a social majority. Here, it is essential to consider that (Bogue, 2005, p.113):

“Majorities and minorities are mutually determined through their positions in power relations, and thus, through their function rather than their possession of some defining trait, whether statistical, religious, ethnic, racial or biological”.

Minor literature has three essential and subsequent characteristics: “the deterritorialization of language, the connection of an individual to a political immediacy, and the collective assemblage of enunciation” (Deleuze, Guattari, 1986, p.18). To expand this concept to all minor works, it is possible to translate these principles to: the deterritorialization of concepts, the critique of power relations, and the creation of new possibilities.

The process of deterritorialization, as mentioned earlier in this chapter, refers to the ruptures of territories, by experimenting with assemblages and giving them new meanings. Some of these experimentations will threaten the existing power relations, which in itself is a political act, evidencing the differences of privilege between the major and minor groups of society.

By deterritorializing and promoting political action, the minor creates new possibilities for upcoming generations, through a process of becoming-other (Bogue, 2005, p.114). This term is used by Deleuze and Guattari because it implies on the minor author creating a voice that doesn’t exist yet: it’s not trying to be the voice of the majority, which the power the author seeks to subvert; neither it is the existing un-heard voice of the minority; but a third possibility, where more options can emerge and open paths that were previously blocked.

Figure 10: Jo Clifford playing the role of Jesus in her play The Gospel According to Jesus: Queen of Heaven (Wright, 2019), an example of minor theatre where Jesus comes back to earth as a trans woman.

Therefore, the minor practice is an example of an act of freedom, where an individual (in this case, a minor author) uses their agency to question power relations, and create new possibilities by experimenting, or folding, the current territories. These new ways of existing (subjectivities) are part of a bigger rhizome system, where they coexist with many other simultaneous possibilities, in a constant dynamic process.

Chapter 3: LGBTQ+ representation, agency and transgressiveness

This chapter will focus on giving a contextual background about the art of drag, analyzing it through post-structuralist theories around agency, production, and gender performance, discussed in the previous chapters.

This section will also explore mainstream LGBTQ+ representation in Brazilian culture, focusing on key figures that were relevant in the second half of the 20th century. It will consider how and why they were folded into popular culture, and whether or not they contribute to transgressing any social construct.

Drag, agency, and gender performance

Drag, as the act of one disguising themselves to represent another gender, has existed for centuries in society, especially when referring to the act of men dressing up to perform as women. Being either secular or sacred, records of these manifestations date back to ancient Greek theatre – in Western society – and to classic Chinese and Japanese theatre – in Eastern culture. (Baker, 1994).

These performances first gained the name of ‘drag’ in 1887, according to the Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (1984, p.338), referring to “the petticoat or skirt used by actors when playing female parts” that would drag across the floor, unlike the pants other actors performing male parts would wear.

The author Roger Baker called these kinds of theatre performances “real disguises” (1994), which is when an actor that plays a woman on stage is understood as a real woman (instead of a man dressed as a woman) by the other actors and the audience. This is not because the transformation is so accurate that the public and actors are fooled by the performance, but it is because the fact that behind the female character there’s a man is not part of the narrative.

Figure 11: John Travolta (left) as Edna Turnblad in Hairspray (2007), a contemporary example of real disguise (James, 2007).

Baker (1994) mentions that real disguises only existed until the late seventeenth century (with some exceptions as seen above) when women weren’t allowed to act in theatrical plays. More than a change of legislation, the introduction of women to the theatre space evidenced what Foucault (Oksala, 2011, p.90) appoints as the productive nature of power. The economic and structural transformations in society at the time created a new power dynamic between men and women, in which gender roles were being revised, as were the societal and familial organizations (Baker, 1994).

From this point onwards, it becomes more frequent to have what Baker describes as “false disguise” (1994), which is when there is no intention from the performer to pretend to be anything else but a man dressed as a woman – or vice-versa. The artist can make it evident by the choice of name, comments made on stage, or some behavior and/or aesthetic. However, there are some which leave the “mystery” open, as the author confirms: “The drag queens can tell the audience where to look, or he can leave a choice open” (Baker, 1994, p.14).

Figure 12: Pamella Sapphic (2020), a drag queen who chooses to make her false disguise apparent through visual elements like beard and chest hair.

In a false disguise performance, the performer’s agency over their production is evident by the decisions they make in constructing their character – or the assemblage they build the territory of their persona with, which includes the choice of creating (or not) the “mystery” that Baker (1994) mentions.

In most cases, false disguise is also an example of minor production. It’s usually produced by a member of a minority group (in most cases an LGBTQ+ person or a heterosexual cis woman) to challenge or mock gender norms and create new possibilities for gender performance.

The art of false disguise drag is also an exercise of Foucaultian freedom (Todd, 2011, p.112): not only they’re practicing agency over their actions and, therefore, performance; but also showing their consciousness as a subject over the power relations that undermine their actions. In this case, the power relations that constructed the concept of gender and gendered behaviors.

Moreover, when a drag queen chooses to put together a character that resembles a woman, they’re proving Butler’s (1988) views on the artificiality of gender: to perform a certain gender, one only needs a series of elements and symbols (visual and non-visual) that were socially constructed to be attributed to that gender.

In the same way, drag queens with more androgynous aesthetics are also bending the limits of gender performance by de-territorializing assemblages belonging to one gender or the other and re-assembling them to create their persona.

The popular TV reality shows RuPauls’ Drag Race (2009) helps to fold these ideas surrounding gender performance and its flexibility into the mainstream culture. By filming the contestants in drag, out of drag, and getting in drag, the show evidences the difference between the character and the individual and also highlights the moments when the characters are being performed (the runways, lip-sync battles, acting challenges, etc).

Additionally, RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009) challenges the social and historically built discourse that associates sex to sexuality and gender, appointment by Foucault (1990, p.151) in Chapter 1, by having gay cis-males and straight trans-women (amongst others) performing gender in a plurality of ways.

Figure 13: Contestant from RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009) Season 11 out of drag during the show.

The reasons above describe ways in which RuPaul’s’ Drag Race (2009) is transgressive. However, the show was only able to be folded into popular culture by compacting the complex world of drag into acting challenges, sewing contests, and beauty pageants that separate participants into winners and losers, according to the judges’ subjective views. The TV program uses formats that exist in the entertainment industry to become part of it, navigating the power structures already in place to insert thematics that otherwise would be reserved to the LGBTQ+ underground scene.

For its transgression and its popularity, RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009) follows Deleuze and Guattari’s (1986) logic of minor productions: it opens a path that was previously blocked within the mainstream entertainment industry for upcoming generations of performers.

LGBTQ+ culture, community, and representation in Brazil

João Silvério Trevisan describes the Brazilian reality as diving into an enigma made of superlatives (2018, p. 47). These superlatives can be sometimes positive, like hosting the biggest LGBTQ+ parade in the world (Mídia Ninja, 2019), which seems like a very far off reality from growing homophobic crime rates, as indicated by Grupo Gay da Bahia (2018), with one victim every 19 hours. Brazil also has the highest number of assassinations of transgender people (Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide, 2016) – who have a life expectancy of 35 years in the country (Thomaz, 2018); at the same time that it is the country that most searches for trans-related pornography (Querino, 2018).

In this tumultuous context, however, there is also permissiveness. As mentioned in the previous chapters, social structures and apparatuses like the rhizome and the fold – described by Deleuze and Guattari (1988, p.8) – allow for contrasting ideas to co-exist in society. Even if homophobic power structures are in place – manifested by political and social institutions – the LGBTQ+ community found a way to create their own deterritorialized territories and cultivate their culture in the margins of society.

This permissiveness is, of course, dependent on shifting socio-historical values. It allowed for some symbols and key figures of LGBTQ+ culture to make their way into the mainstream, under certain conditions which will be discussed in this chapter. Trevisan (2018) adds that the social permissiveness is opportunist and that the tolerance varies from time to time, depending on external factors that add to the homosexual practice a greater or smaller degree of dangerousness, according to the circumstantial needs.

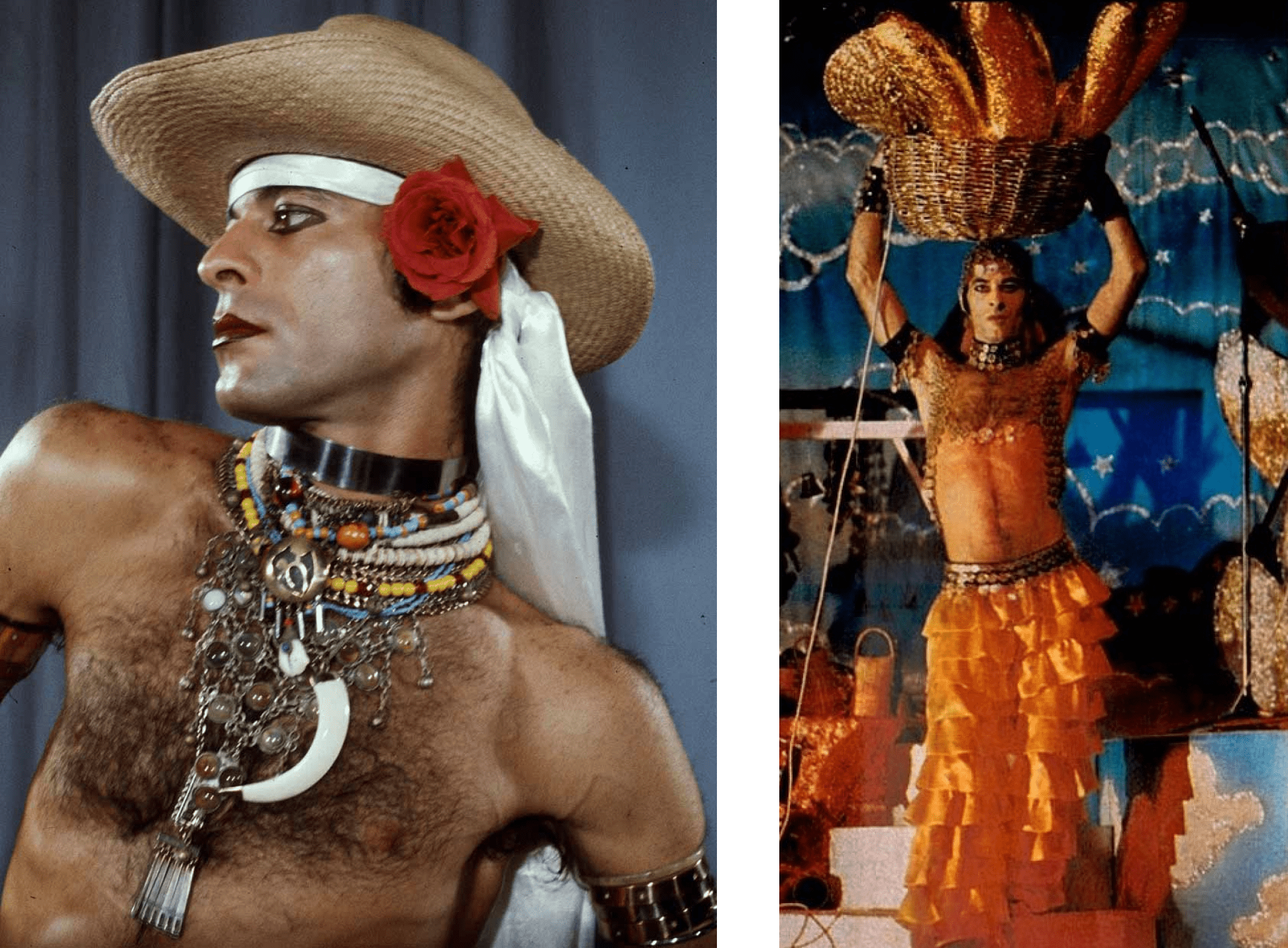

One of Brazil’s most popular LGBTQ+ icon is the singer and composer Ney Matogrosso. Ney is an example of minor performance, according to the Deleuzian concept, by being a gay man who, amid military censorship, was able to deterritorialize gendered fashion and behavioral constructs through his artistic productions. He critiqued the power relations in his music that constantly mocked masculinity, and disassembled the symbols of masculinity and femininity in his looks, creating a new androgynous subjectivity (Trevisan, 2018). Matogrosso was seen almost as a fantastic creature, which helped him to be folded into mainstream society. In his process of becoming-other, Ney became so different from what was seen in popular culture, to the point that the public saw him as an exotic being – something so foreign that almost existed “apart” from the rest of society.

Figure 14, left (Maia, 1970) and 15, right (Noize, 2014): Looks from Ney Matogrosso circa 1970, displaying his androgenous looks that mixed feminine and masculine elements.

Another key figure in the recent history of LGBTQ+ mainstream representation in Brazil was comedian Jô Soares’ character Captain Gay (Capitão Gay, 1981). This superhero wore a pink feathery gown and solved problems “no man or woman could solve” (1981) with the aid of his phallic magic wand. Although the character was transgressive by mentioning homosexuality in a popular television show during the 80s and associated a gay figure with a hero (and not villain), this was not a minor production. Beyond the fact that Jô is a straight man, Capitão Gay only re-affirms the constructed subjectivity of the homosexual man, using an assemblage that associates homosexuality with femininity.

The character is also an example of one of the ways LGBTQ+ figures were folded into Brazilian popular culture: as the punch line of the joke (Trevisan, 2018). It is not unusual to see LGBTQ+ characters in Brazilian TV shows as satirical personas. This promotes a subjectivity – that is, “a way of being” gay – that restrained the roles, behaviors, and appearance an LGBTQ+ person could have in society.

Figure 16: Capitão Gay, wearing a famous pink costume and mask (O Globo, 1981).

Therefore, in recent history, the two main ways that LGBTQ+ representation existed in Brazilian popular culture was either as an exotic figure, like Ney Matogrosso or as a satirical figure, like Capitão Gay. These were two subjectivities that were folded into the mainstream and grew as long ‘shoots’ in Brazilian society’s rhizome for placing LGBTQ+ figures on the outside of the fold. They were ‘others’, either to be looked at or laughed at. Trevisan (2018) called this process a “mandatory hygienization” of LGBTQ+ culture for it to become palatable to the general public.

Simultaneous to these nation-wide known figures is the LGBTQ+ underground scene. In this liminal space, transformist actors (Trevisan, 2018), the Brazilian precedent to drag queens, have agency to create their own performances that don’t need to be comical or exotified (if they don’t want to). Some of these transformists, like Marcia Pantera (Figure 16), use an assemblage of elements that communicates standard ideals of femininity in their performance – and reveal the performative character of gender described by Butler (1988).

Figure 17: Marcia Pantera using her signature long wigs and breastplates, to compose the figure of a hyper-feminine drag persona. (Pantera, 2020).

In her act, Pantera also challenges the existing subjectivities for public LGBTQ+ figures in Brazil. By performing a version of femininity that is considered to be desired and even sexualized, Marcia is not being neither satirical nor exotified. In this underground space, the drag queen is using her agency and minor production to create new folds in society, in which the LGBTQ+ community can exist in ways that go beyond the one-dimensional figures mainstream society presented to them.

Chapter 4: Case study - Pabllo Vittar

Pabllo Vittar is one of Brazil’s biggest contemporary pop icons and on the list of most famous drag queens in the world. Phabullo Rodrigues da Silva, the person behind the character, started doing drag at age 16. At that time, he only knew about the drag scene that involved the lip syncs battles at gay nightclubs, until a boyfriend of his presented Phabullo to RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009) and he got to know the multiple kinds of drag performers and performances there are. From there, Phabullo joined his passion for singing – something he cultivated since childhood – and the art of drag to begin performing as Pabllo Vittar (Finco, 2017).

Performance, agency, and folds

Vittar’s success is undeniable. She’s currently the world’s most-followed drag queen on Instagram (Dias, 2020), was the first-ever drag to be nominated for a Grammy (Querino, 2018), and first to sing at the United Nations, with the support of the British government (5 innovations the UK has supported alongside our international partners, no date). Vogue has also overviewed her fame with numbers (Codinha, 2018):

“[…] she released a new album, Não Para Não (“No, Don’t Stop”), which hit the top of the Brazilian iTunes charts in less than two hours: The first single, “Problema Seu,” reached 40 million YouTube views in less than two months; the video for her track “Disk Me” hit 5 million views on YouTube in less than two days; all 10 songs off the album charted in Spotify Brazil’s Top 40 most streamed songs within hours.”

Pabllo’s career rise evidences how she was able to use her Foucaultian’s freedom to navigate the power structures that, in Brazil’s conservative context, limited her reach. She got her first appearance in mainstream media as the singer of the band in the late-night show Amor & Sexo (2009), in 2016. By the prevailing social norms that associate the LGBTQ+ community to marginality, with the exceptions of ‘the permissive opportunism’ described by Trevisan (2018), the TV Show was seen as an ‘appropriate space’ to have a drag queen, since it was dedicated to discussing liminal and taboo subjects – such as sex and sexuality. Nonetheless, this was an opportunity for Pabllo to show her performance to a greater audience.

Figure 18: Pabllo Vittar performing at the Carnaval street party Pop do K7 (Justo, 2017).

Under these conditions, Vittar didn’t have full agency over her performance: her outfits were chosen by a stylist, and followed the theme of the episode of the week, as did the selected setlist of songs Pabllo sang. However, in 2017, the performer released the Carnaval hit song ‘Todo Dia’, which led her to the country’s top charts (Billboard Brasil, 2017).

Todo Dia took advantage of the temporal flexibility of social values that composes Carnaval’s territory. It allows for a temporary elevation of morals regarding cross-dressing and sexuality, but only the cis-heteronormative kind. Todo Dia deterritorializes this by being one of the first Carnaval hit songs that have LGBTQ+ sexuality at its center; written by a gay man, Rico Dalasan, and sung by a drag queen, Pabllo Vittar. While its transgressive character is undeniable, Todo Dia’s popularity can be attributed to the social and temporal context (Carnaval) in which power relations dynamics were configured in such a way that allowed the agents (Rico and Pabllo) to exercise their freedom and experiment with their artistic production.

Following the Carnaval’s success, Pabllo was featured in Sua Cara (2017), a collaboration between Anitta and Major Lazer. Here, Pabllo is being placed next to popular culture icons, national and international (consecutively), whose productions are made and reproduced outside of the liminal space where Pabllo used to perform, up until recently. Being associated with these mainstream personalities facilitated Vittar’s fold into the mainstream. She began to detach herself and her image from places where her presence as a drag queen could be expected and accepted, like the TV Show Amor & Sexo (2009) and the liberal times of Carnaval; to putting her persona in the position of a pop diva, next to Anitta.

Figure 19 – Anitta (top left), Diplo (center) and Pabllo (bottom right) in the music video Sua Cara (2017).

However, even if in Sua Cara (2017) Pabllo’s performance continues to be a false disguise, her appearance and aesthetics are a key point in Vittar’s process of being folded into mainstream culture. Much like many contemporary drag queens, Pabllo’s makeup and looks are far from the ones used in an assemblage of a camp queen. She performs a very female-presenting persona, using a series of assemblages that compose the contemporary territory of the young woman. These have changed over time, as this is one of the founding principles of assemblages and territories, as mentioned in Chapter 2. Therefore, instead of using breast-plates and hip-pads, Pabllo’s assemblage of femininity includes long wigs, full lips, a lean and thin figure, high pitched voice, and long nails, to name a few. Unlike camp queens, who take those feminine features and exaggerate them with a satirical intention, Pabllo uses those features to mimic the idealized and propagated version of femininity, so much so that she was able to acquire a certain ‘passability’ as a woman.

Figure 20 (left) and 21(right): Captions of viewers mistaking Pabllo for a woman. On the left, the comment says “This blond with Anitta is beautiful and hot. This Pabllo Vittar does nothing, just stays on top of that tricycle, someone knows the Instagram of the blond?” (Me. Me, 2017) And on the right, it says ” I don’t know this Pabllo Vittar, but I know that he’s got lucky, look at the beautiful blond he’s with, congratulations” (Vingay, 2017).

Pabllo’s acquired ‘passibility‘ as a cis-woman to the unaware public is an advantage to her integration into mainstream culture. The term “unaware public” here refers to a big part of Brazilian society that is unfamiliar with LGBTQ+ culture and its manifestations, such as drag. They would be the ones to automatically associate behavior and appearance to a natural, given gender, and not one that can be performed. By this unaware public seeing Pabllo look and behave like what fits into their concept of a woman they believe they’re indeed seeing a woman.

This ‘passability’ issue has gone to the extent of Vittar being nominated or awarded to females (F5, 2017) and trans categories in awards. In 2017, when Pabllo was asked about her gender identity she answered:

“[The character Pabllo] comes from a boy who is gay, who is a man, who is homosexual, who is gender fluid, who likes to transit between the feminine and the masculine […] because I don’t care if people call me o Pabllo, a Pabllo, I think gender is something that stayed in the past and we have to believe we can be anyone, independent from our sexual organ, our sexual orientation” (Vittar, 2017).

However, when the performer was notified of her most recent victory as Miss Bumbum Transsex 2019 (Miss Butt Transex 2019), Pabllo published a video on her social media denying the award and stating that “Everyone knows I’m a man in a wig, a crazy gay man” (2019, quoted in @skipvall, 2019). She also answers in her “Most googled questions” video (Google, no date): “When I’m dressed as a boy you can call me ‘he’ when I’m dressed as a girl you can call me ‘she’. I didn’t spend one hour putting on makeup for you to call me a man”.

Identifying herself as gender fluid or not, it is possible to say that Pabllo understands the concept of gender as a variable performance, as Butler (1988) theorizes. She associates the pronoun to the gender she is performing at a given time and place, according to her assemblage: “I’m a drag queen only when I have to be. It is like a hat: I put it on and off when I need to. I’m not a drag 24 hours” (Vittar, 2017).

Vittar also reinforces the performative character of gender (and of her persona) to the public when, as an active agent, she evidences her false disguise. Besides going against what most drag queens do, Pabllo purposely chose a “boy’s name” for her character, affirming that opting for a “woman’s name” would never communicate her true self (F5, 2017). In other words, reaffirming that she doesn’t wish to be seen as a woman, but as an individual who has agency over their gender performance.

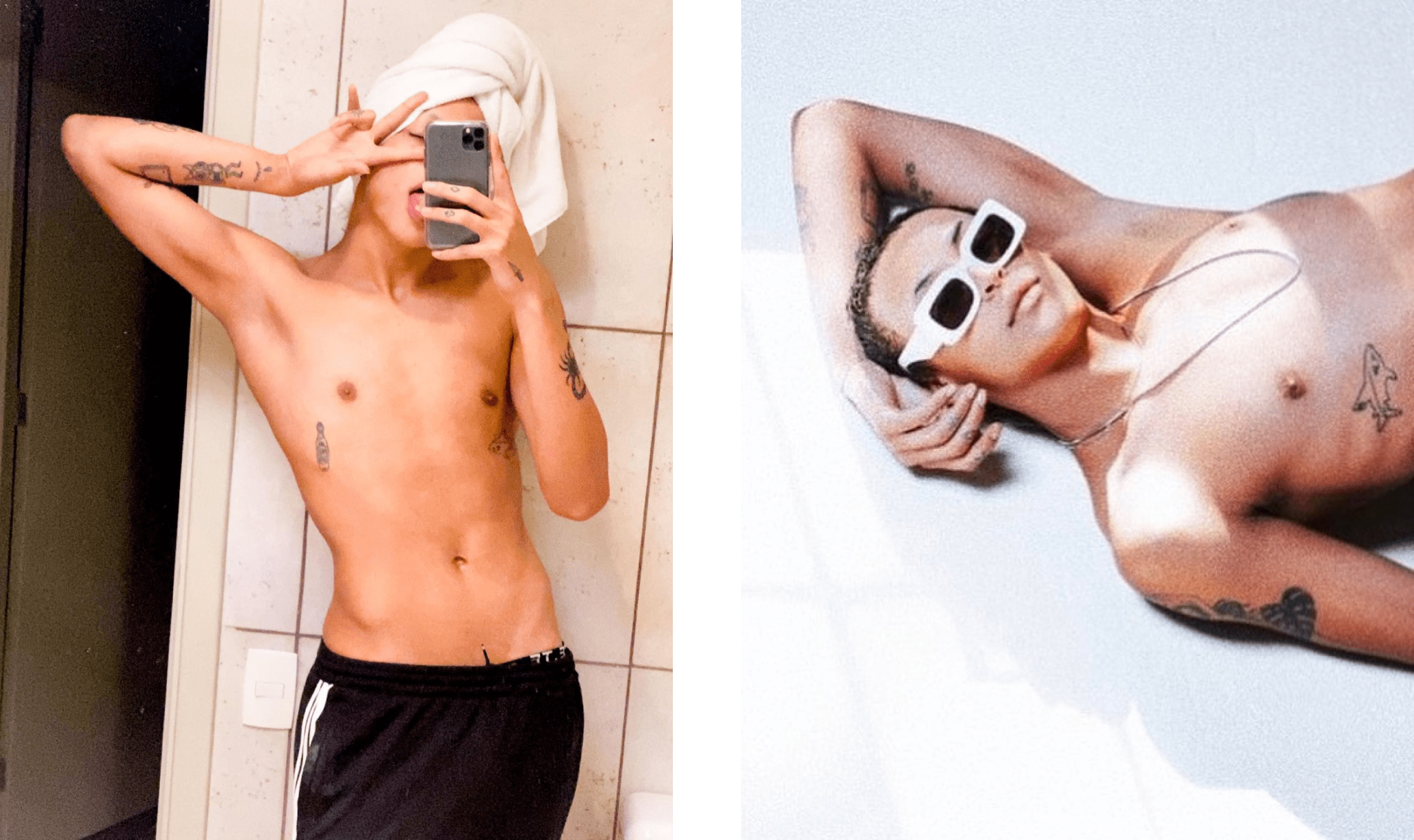

Another way in which Pabllo evidences her false disguise act is on social media. There, Vittar is constantly seen out of drag, speaking to her audience on the “stories” feature, rehearsing choreography on her profile’s feed, in her free time, and even in mid-drag stages (when she is just wearing parts of the elements that compose the character). She constantly reminds her public of the assemblage that constitutes her character, and how that territory is constantly being constructed and deconstructed through her appearance.

Figures 22, left (Vittar, 2020) and 23 (Vittar, 2020): Example of Pabllo’s photos out of drag that she has published on her Instagram.

Pabllo Vittar’s folding in comparison with other contemporary drag artists

This part of the chapter aims to discuss how and why Pabllo reached this high level of success, while other contemporary drag queens, who share similar aesthetics, weren’t as folded into mainstream culture as Pabllo.

Pabllo Vittar, Gloria Groove, and Lia Clark are all singers and drag performers who began reaching recognition in the LGBTQ+ Brazillian community around the same time. While Pabllo hit the charts in 2017 with Todo Dia (2017), Gloria Groove released her debut album, O Proceder (2017), and Lia Clark was thriving with her niched Carnaval single Chifrudo (2017).

They all also share a similar choice of visual assemblage for their characters: female-resembling personas, with a softer make-up that mimics the aesthetics of young women and pop divas, stepping away from the camp or androgenous drag style, and without using any padding to alter their body shape.

Figures 24 (Groove, 2020) and 25 (Clark, 2020): Gloria Groove (left) and Lia Clark (right).

The other elements of their assemblage (like the choice of performance, music style, lyrics, and partnerships) are what made them more or less folded into Brazilian popular culture. However, it is important to notice that all three artists are minor performers, for reasons that will be discussed ahead.

One of the main differences between Pabllo and Gloria is the fact that the latter uses black and urban-peripheral culture as part of her performance, which is manifested in various parts of her assemblage: using braided wigs, the eyebrow slits, the slangs and references used on her lyrics, and even doing mainly rap, hip-hop, R&B, and funk songs, which are cultural productions from the black community. As an active agent, Groove uses her performance space to promote racial and social agendas, challenging the social-historical racial-economic power structure that is in place in Brazilian society, which is still racist; and creating a fold in which black LGBTQ+ peripheral people have a representation – configuring Gloria’s performance as a minor production.

Figure 26: Gloria Groove in her funk music video for Coisa Boa (Gloria Groove, 2019).

Even though Pabllo’s ethnicity was never made clear, she, as an active agent over her production, chooses not to use any racialized elements in her assemblage and, more often than not, adding features more commonly seen in white people – like straight blond hair, light eyes, and thin nose.

Lia Clark, on the other hand, is a drag queen who constantly uses LGBTQ+ specific references in her performance to address the community’s reality, aiming to communicate directly to them. Her music style is Brazilian funk, which is associated with peripheral urban-communities (like favelas). However, funk music is usually a straight-male dominated space, where sexism and homophobia are present. Lia’s production can be considered a minor performance, because her presence in this genre challenges power structures that kept the LGBTQ+ community outside of this universe, by explicitly discussing non-heteronormative sexuality in her lyrics and performance. Through the process of becoming-other, Clark creates a new subjectivity in which the LGBTQ+ individual has space and representation within funk culture.

In her lyrics and music style, Pabllo – differently from Gloria and Lia – doesn’t address any specific agenda. Instead, in a big part of her production, she chooses to talk about relationship issues (K.O. (2017), Eu Vou (2020)), messages of hope (Rajadão (2020)) or praising a body part, like a big part of popular female contemporary Brazilian singers.The journalist Tony Goes (2017) confirms this and even adds that most of her lyrics could also be sung by national or international cis-female singers.

Figure 27: Lia Clark (on the right, wearing orange) recording her music video for Berro (Heavy Baile, 2017), along with the funk singer Tati Quebra Barraco (on the center, wearing pink) and the funk collective Heavy Baile (Rosenblatt, 2017).

In her song style choices and artistic partnership, Pabllo – as previously mentioned – generally chooses to make features with mainstream artists, like Anitta, Ludmilla, Charli XCX, and Diplo, to associate her image with them instead of famous minority representatives. Vittar mostly sings pop, with influences from regional Brazilian rhythms, and most recently reggaeton, in an attempt to reach other Latin-American audiences (EFE, 2020).

In comparison with Lia Clark and Gloria Groove, who produce minor performances that are actively associated with minorities, it is possible to observe that Pabllo’s exploration of power structures led to her fold into the mainstream by using existing territories – of music, performance, and aesthetic – which, along with shifting social values, allowed her to reach a level of fame that her contemporary drag colleagues didn’t. Instead, they created their own folds, which are not part of popular Brazilian culture at this point in history.

Pabllo Vittar and her transgressiveness

As mentioned in Chapter 2, minor productions are intrinsically transgressive for challenging current power structures that were imposed by social conducts, historically built. They create ruptures with the norm, giving voice and representation for a collective of individuals that are historically limited by their position in power relations (and, therefore, minorities). Minor productions are a key element to the dynamism of history because they create new folds – the social apparatus that Deleuze (Conley, 2005, p.172) describes as being responsible for resistance and transgression.

Although Vittar chooses not to embrace minority symbols and references in her performance, she can still be treated as transgressive and a minor cultural production. Having an LGBTQ+ person as an icon in Brazilian popular culture can already be considered transgressive itself, considering the country’s historic and current violence against minorities. Pabllo not only existing, but having agency over her production is transgressive since it classifies her performance as a minor production and demonstrates her exercise of freedom, described by Foucault (Todd, 2011, p.80).

The art of drag is one that indefinitely requires the individual’s agency, to build their persona, practicing their freedom on the deterritorialization of gender’s assemblages and choosing the kind of performance they’ll do. Pabllo goes further than that. Not only does she have agency over the persona she created, but she also has direct creative input in her career – different from many famous pop artists. She is an active part of the creative process in her music videos, as the director of Parabéns (2019) and Bandid* (2020), scriptwriter of Rajadão (2020), a makeup artist in Clima Quente (2020), creative director of Amor de Que (2019) and creating the treatment for Seu Crime (2018), to name a few. She also contributes to writing in some of her songs and has agency over her public image on the media – like on interviews and social media.

As a public figure, Pabllo is not absent in political discourses and uses her social media and public image to promote LGBTQ+ agendas – even if she doesn’t do this actively in her on-stage performance and music career, like Gloria Groove and Lia Clark. She also uses her space in the music industry to promote national rhythms (like brega and forró) and independent artists – like in her Deluxe version of her latest album 111 (2020), exclusively featuring remixes of her songs by up-and-coming artists.

Vittar is transgressive in assuming a place in cultural production that is not usually given to LGBTQ+ personalities in the current socio-political structure. During her career, she has practiced her freedom in experimenting with the opportunities that were presented to her according to the current social power dynamic she was experiencing. In retrospect, it is possible to see that the outcome of this practice was positive – as suggested by Focault’s (Todd, 2011, p.80) concept of freedom.

Even in Pabllo’s choice of gender performance, which at first sight, might seem to corroborate with the standardized and idealized territory of women, she is still being transgressive. Like Marcia Pantera, Vittar is performing a version of femininity with no intention of being satirical or exotified, but instead of remaining in the liminal space of the LGBTQ+ culture, she reached mainstream audiences.

Vittar deterritorializes the assemblage of the sexualized female pop diva from the cis-woman territory, and performs it herself, as a drag queen who insists on evidencing to the public her false disguise. As Goes (2018) puts it, a drag queen with a high pitched voice and a man’s name, who doesn’t care if she’s treated on the feminine or the masculine. The author also adds that Pabllo refuses the role of the “family-friendly gay”, and insists on purposeful sexualization of her body (in and out of drag), even if it’s inconvenient to conservative Brazilian society.

Figures 28, left (Vittar, 2020) and 29, right (Vittar, 2020): Pabllo exhibiting her body in and out of drag.

Pabllo Vittar was folded into the mainstream as a minor production. She is a conscious, active LGBTQ+ agent practicing her freedom by having agency over her performance, which puts into question power relations in regards to the production and representation of LGBTQ+ subjectivities in popular culture, besides evidencing the performative character of gender in her false disguise act. With this, she is creating a fold within the mainstream culture which includes LGBTQ+ culture territories and her version of feminine (and masculine) gender performance; making space for new subjectivities to rise. At the same time, Vittar is also being folded into the mainstream when experimenting with her performance. She uses assemblages that are already part of popular culture, practicing her freedom to navigate existing power structures and promoting change.

Conclusion

After thoroughly analyzing post-structuralist theories over gender, identity, production, and agency, followed by applying them to contemporary cultural productions of drag performance, this work helped me reach a few optimistic conclusions explained in the paragraphs below.

In the first place, Focault’s (Todd, 2011, p.80) view on the practice of freedom describes it as a tool to overcome social constraints put in place due to socio-historical circumstances. It denies determinist theories that place the individual in a powerless position, by considering them an active agent, capable of transgressing the structures that restrict them.

This idea, along with Deleuze’s (Conley, 2005, p.173) construct of the folds, which highlights points of rupture in society, gives a positive panorama for the future in theorizing social apparatuses that explain historical shifts. Pabllo – and drag culture to some extent – being folded into popular culture is proof of Deleuze’s and Foucault’s theories in practice. It evidences that society has shifted to such a point that allows for a drag queen, who has agency over her production, performing a false disguise to reach the level of pop icon in an inherently socio-political conservative country.

Secondly, Judith Butler’s (1988) theory on gender being a performance, which is an expansion of Foucault’s (1990) studies over the historical construct of sexuality, is manifested through the art of drag. Artists, men or women, create a persona through an assemblage that is socially associated with one gender and then perform it as an act. This shows that there’s almost no distinction between what a gender appears to be and what it really is, after all, gender is dependent entirely on performance.

Furthermore, since the art of drag revolves around an individual’s agency over their performance, here lies an opportunity to challenge how gender can be performed. This is done by exaggerating gender constructs with satirical intentions like camp queens do; by doing an androgenous persona, that mixes elements associated with different genders into one act; or by deterritorializing the performance of sexualized femininity and attributing it to a false performance, as Pabllo Vittar does.

And finally, as affirmed in the last chapter, it is possible to conclude that Pabllo Vittar is a transgressive figure. Even if she is performing a kind of femininity that is already well-known within popular culture, and her artistic production lies in the common grounds of pop music, Pabllo is occupying a space that has been historically neglected to the LGBTQ+ community. With that, Vittar is also challenging the current power structures and creating a fold within mainstream media for future generations, as minor productions should do, according to Deleuze and Guattari (1986).

The insights that this dissertation gave me are really important to my career as a creative and to my development as an individual in society. Being aware of the place I take as a minority or majority, depending on the context, will influence on which side I’m positioned in a power relation.

As a creative, I have agency over my production. The subjectivity I occupy in a dynamic power relation will influence my production and the reception it has on the public, since this product is inserted in a socio-cultural historical context.

As an individual in society, it is crucial to know there are ways to change society’s structure and that this idea is not utopic. What post-structuralist scholars like Michael Foucault and Gilles Deleuze do by analyzing these changes through history is to provide us with explanations as to how and why these ruptures happen – and in confirming that if they have happened before, there is no reason as to why they can’t and won’t happen again.

Post-structuralist theories and drag performance themselves prove these movements can happen on a macro or micro scale since transgression doesn’t rely on the reach, but on the agent’s agency over practicing their freedom. Investigating Pabllo Vittar’s career and performance through these lenses proves that structural transgressions can be made, or even start, in artistic and cultural production from groups of society that have been historically neglected and marginalized.

List of References

Albrecht-Crane, A. (2005) ‘Style,Stutter’, in Stivale C.J. (ed). Gilles Deleuze: Key Concepts. Chesam: Acumen, pp. 121 – 130.

Amor & Sexo (2009) Rede Globo, 28 August, 23:00.

Baker, R. (1994) Drag. London: Cassell.

Beauvoir, S. (2009) The Second Sex. Translated from the French by C. Borde and S. Malovany-Chevallier. New York: Vintage Books.

Billboard Brasil (2017) Meet Pabllo Vittar: Major Lazer’s Favorite Brazilian Drag Queen. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Butler, J. (1988) ‘Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory’, Theatre Journal, Vol 40, No. 4, pp. 519-531. Available here (Accessed: 14 November 2020)

Butler, J. (1990) Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Capitão Gay (1981) Viva O Gordo. Rede Globo, 9 March.

Charles, R. (2014) Born Naked. United States: RuCo Inc.

Codinha, A. (2018) What Pabllo Vittar, Pop Superstar, Means to Brazil (and the Rest of Us) Right Now. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Conley, T. (2005) ‘Folds and Folding’, in Stivale C.J. (ed). Gilles Deleuze: Key Concepts. Chesam: Acumen, pp. 170 – 181.

Craig, E. (ed.) (2005) The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. New York: Routledge.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1986) Kafka – Toward a Minor Literature. Translated from the French by D. Polan. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus – Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated from the French by B. Massumi. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Deleuze, G. (1988) Foucault. Translated from the French by S. Hand. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Dias, S. (2020) Pabllo Vittar atinge 10 milhões de seguidores no Instagram: “Nunca imaginei”. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

EFE (2020) ‘Thalía e Pabllo Vittar lançam clipe de ‘Tímida’; assista’. Available here (Accessed: 6 February 2021).

Finco, N. (2017) Pabllo Vittar: tem drag no samba. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Foucault, M. (1979) The History of Sexuality, Vol 1., An introduction. Translated from the French by R. Hurley. London: Allen Lane.

Foucault, M. (1990) The History of Sexuality, Vol 1., An introduction. Translated from the French by R. Hurley. New York: Vintage.

Foucault, M. (1994) ‘The Ethics of Care for the Self as the Practice of Freedom’, in J. W Bernauer and D. Rasmussen (eds). The Final Foucault. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 1-20.

F5 (2017) Prêmio F5: Saiba quem são os indicados e vote nos seus preferidos de 2017. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

F5 (2017) ‘Se eu tivesse um nome feminino, não ia passar tanta verdade’. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Goes, T. (2018) ‘Pabllo Vittar faz política mesmo cantando sobre amor e festa’. Available here (Accessed: 6 February 2021).

Goes, T. (2017) ‘Por que Pabllo Vittar faz mais sucesso que Liniker?’. Available here (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Goodman, E. (2019) What Is Camp?. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Google (no date) Mais frequentes no Google. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Gloria Groove (2017) O Proceder. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Grupo Gay da Bahia (2018) Mortes Violentas de LGBT+ no Brasil. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Hairspray (2007) Directed by Adam Shankman [Feature film]. United States: New Line Cinema

Heyes, C.J. (2011) ‘Subjectivity and Power’, in Taylor D. (ed). Michael Foucault: Key Concepts. Durham: Acumen, pp. 159 – 172.

Jerry Smith, Pabllo Vittar (2020) ‘Clima Quente’. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Katz-Wise, S. L. (2020) ‘Gender fluidity: What it means and why support matters‘. Available here (Accessed: 4 February 2021)

Heavy Baile (2017) ‘BERRO (feat Tati Quebra Barraco e Lia Clark)’. Available at: YouTube (Accessed: 44 January 2021).

Lia Clark (2017) ‘Chifrudo (feat. Mulher Pepita)’. Available at: YouTube (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Luana (2019) [@skipvall] 17 July. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Major Lazer, Anitta and Vittar, P. (2017) Sua Cara. Available at: Spotify. (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

May, Todd (2011) ‘Foucault’s Conception of Freedom’, in Taylor D. (ed). Michael Foucault: Key Concepts. Durham: Acumen, pp. 71 – 83.

Mídia Ninja (2019) A maior do mundo: confira as imagens da 23ª Parada do Orgulho LGBT de SP. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Mirriam-Webster (no date) Campy. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Mullen, M. (2019). The Pink Triangle: From Nazi Label to Symbol of Gay Pride. Available here (Accessed: 18 January 2021).

Neves, F. (no date) ‘Artigo definido’. Available here (Accessed: 4 February 2021)

Oksala, J. (2011) ‘Freedom and bodies’, in Taylor D. (ed). Michael Foucault: Key Concepts. Durham: Acumen, pp. 85-97

Pabllo Vittar (2017) ‘K.O.’ Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar (2018) ‘Seu Crime’. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar (2019) ‘Amor de Que’. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar, Psirico (2019) ‘Parabéns’ Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar, POCAH (2020) ‘Bandid*’ Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar (2020) ‘Eu Vou’. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar (2020) ‘Rajadão’. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Pabllo Vittar (2020) ‘111 DELUXE’. Available at: Spotify (Accessed: 4 February 2021).

Partridge, E. (1984) A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. Edited by Beale P. London: Routledge

Querino, R. (2018) Pabllo Vittar se torna a primeira drag queen a ser indicada ao Grammy Latino. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Querino, R. (2018) País que mais mata trans no mundo, Brasil é também o que mais acessa pornôs do gênero, reforça pesquisa. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009) VH1, 2 February, 20h. Available at: Netflix (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Serrano, J.L., Caminha, I. O., Gomes, I.S., Neves, E. M. and Lopes, D. T. (2019) ‘Transgender women and physical activity: fabricating the female body’, Interface – Comunicação, Saúde, Educação, vol. 23. doi: 10.1590/180624

Schwarcz, L.M. (2010) Racismo no Brasil. São Paulo: PubliFolha.

Taylor, D. (2011) ‘Introduction: Power, Freedom and Subjectivity’, in Taylor D. (ed). Michael Foucault: Key Concepts. Durham: Acumen, pp. 1-9

Thomas, D. (2018) Reduzida por homicídios, a expectativa de vida de um transexual no Brasil é de apenas 35 anos. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Trevisan, J.S. (2019) Devasso no Paraíso. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva.

Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide (2016) TMM annual report 2016. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

If I had the words to tell you we wouldn’t be here now by V. Sin [Chi-Wen Gallery. 2019]

Vittar, P. (2017) ‘Como um garoto que cresceu sofrendo bullying no MA se tornou Pabllo Vittar’. Interviewed by Carmo P. for Folha de S. Paulo, 6 August. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Vittar, P. (2017) ‘Pabllo Vittar fala sobre clipe, sucesso e gênero em entrevista’. Interviewed by Jatobá, T. for Folha de Pernambuco, 7 August. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Wise, J.M. (2005) ‘Assemblage’, in Stivale C.J. (ed). Gilles Deleuze: Key Concepts. Chesam: Acumen, pp. 77 – 87.

White Chicks (2004) Directed by Keenen Ivory Wayans [Feature film]. Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures

5 innovations the UK has supported alongside our international partners (no date). Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

List of Figures

Figure 1

Fewings, T. (2020) Divina De Campo was among the most popular queens. Available here (Accessed: 19 November 2020).

Figure 2

Davies, D. (1969) Gay Liberation Front Marches on Times Square, New York City, 1969. Available here (Accessed: 19 November 2020).

Figure 3

London Metropolitan Archives (2019) Campaign for Homosexual Equality poster. Available here (Accessed: 19 November 2020).

Figure 4

Valentim, D. (2019) ‘Do lar’ [Instagram] 26 November. Available here (Accessed: 21 November 2020).

Figure 5

Duclos. A. (1996) Rupaul Store Opens In London Mac On April 19th, 1995. Available here (Accessed: 13 January 2021).

Figure 6

Aquaria (2020) ‘cherry vanilla cola pow pow’ [Instagram] 4 July. Available here (Accessed: 13 January 2021)

Figure 7

White Chicks (2004) Directed by Keenen Ivory Wayans [Feature film]. Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures.

Figure 8

White Chicks (2004) Directed by Keenen Ivory Wayans [Feature film]. Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures.

Figure 9

Personal archive (2020) Illustration of Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizome.

Figure 10

Wright, A. (2019) Jo Clifford in The Gospel According to Jesus Queen of Heaven. Available here (Accessed: 13 January 2021).

Figure 11

James, D. (2007) John Travolta and Nikki Blonsky in the 2007 film “Hairspray.” Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021).

Figure 12

Sapphic, P. (2020) ‘Eu te amo, mas não deixo você me destruir’ [Instagram]. 19 July. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021).

Figure 13

RuPaul’s Drag Race (2009) VH1, 2 February, 20h. Available at: Netflix (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 14

Maia, J. ( circa 1970) Ney Matogrosso, o showman brasileiro. Available here (Accessed: 7 January 2021).

Figure 15

Noize (2014) Os 10 Figurinos Mais Insanos de Ney Matogrosso. Available here (Accessed: 7 January 2021).

Figure 16

O Globo (1981) Em Foco: Jô Soares e Seus Personagens. Available here (Accessed: 7 January 2021).

Figure 17

Pantera, M. (2020) Untitled. Available here (Accessed: 7 January 2021).

Figure 18

Justo, G. (2017) Pabllo Vittar canta em bloco. Available here (Accessed: 7 January 2021).

Figure 19

Major Lazer, Anitta and Vittar, P. (2017) Sua Cara. Available at: Spotify. (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Figure 20

Me.Me (2017) Untitled. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Figure 21

Vingay (2017) [Facebook] 27 December. Available here (Accessed: 1 February 2021)

Figure 22

Vittar, P. (2020) sextou [Instagram] 11 September. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 23

Vittar, P. (2020) BOYFRIEND [Instagram] 6 August. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 24

Groove, G. (2020) #DeveSerHorrivelDormirSemMim ainda mais nesse friozuxo […] [Instagram] 22 August. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 25

Clark, L. (2020) diria não pra uma gaymer dessas? [Instagram] 30 July. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 26

Gloria Groove (2019) Gloria Groove – Coisa Boa. 10 January. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 27

Rosenblatt, V. (2017) DJ Thai, Tati Quebra Barraco, MC Tchelinho, Leo Justi & Lia Clark. Berro – Heavy Baile feat Tati Quebra Barraco & Lia Clark – Video. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 28

Vitta, P. (2020) Pretty SAVAGEEEEEEEEE [Instagram] 25 October. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)

Figure 29

Vittar, P. (2020) Golden girl [Instagram] 29 August. Available here (Accessed: 24 January 2021)